The days are getting longer now.

The solstice came in sweetly on a Saturday, a day for friends old and new, a time to indulge in rich sustenance and awaken the soul from the darkness. Meats of all sorts were devoured, cooked decadently on a smoker sixteen feet long. The side dishes were tantalizingly delicious but required quick eating, as they froze in the single digit temperatures. Mulled wine was poured to aid in the warming, as buttered rum made its rounds from a thermos slung over a shoulder. A Master Sommelier, clad in his insulated Carhartt coveralls, read aloud a poem, aptly titled "Shortest Day,” by Susan Cooper. As the temperatures plummeted we encircled the fire, hearty humans dressed in our warmest of layers, just as people did in our beginnings - telling stories.

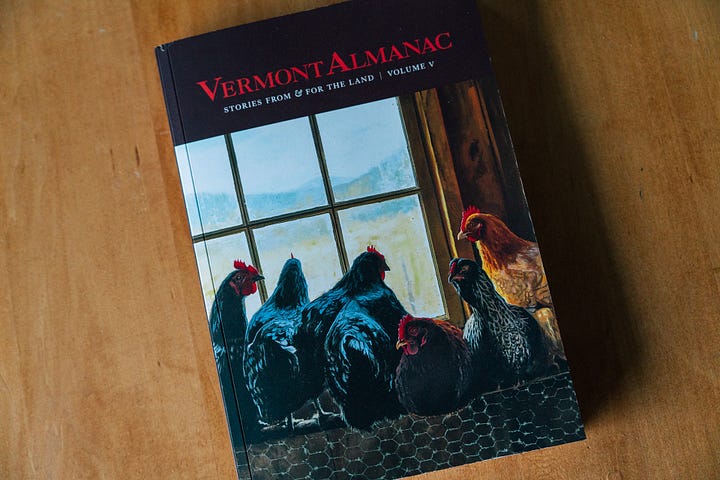

Earlier in December, on a night almost equally as frigid and dark, I peeled myself away from the comfort of the wood stove, venturing towards the capital city. I had been invited to the book launch for Vermont Almanac, Volume V, in which I had published a story about last year’s moose hunt. From my little home, tucked on the northwestern flanks of Mount Mansfield, I wove between the mountains and through the valleys, making my way to the smallest capital “city” in America: Montpelier, population 8074. As I travelled the snowy roads I thought of the New England phrase “you can’t get there from here,” which often feels so close to true in these parts. I winced as my Tacoma put on the miles, making its way around the craggy walls and rounded peaks of Vermont’s Green Mountains.

En route to the book launch I stopped to pick up my childhood friend Jessee Lawyer. Jessee is Abenaki and an executive chef, bringing attention to traditional foods and preparation techniques in our state. He provides cooking demonstrations for Vermont Fish and Wildlife using native ingredients, and has been published in books such as Meat Eater’s “Outdoor Cookbook.” As kids we grew up next to the Canadian border, in one of those end-of-the-road sorta towns. We did the normal small town kid stuff - played sports, drove too fast, and jumped into swimming holes. As adults we’ve been brought together by the sharing and stewarding of food and animal resources: native flint corn and beans, bear pemmi (fat), deer hides and hooves… the list goes on. If you want to know how to use any part of an animal, ask Jessee.

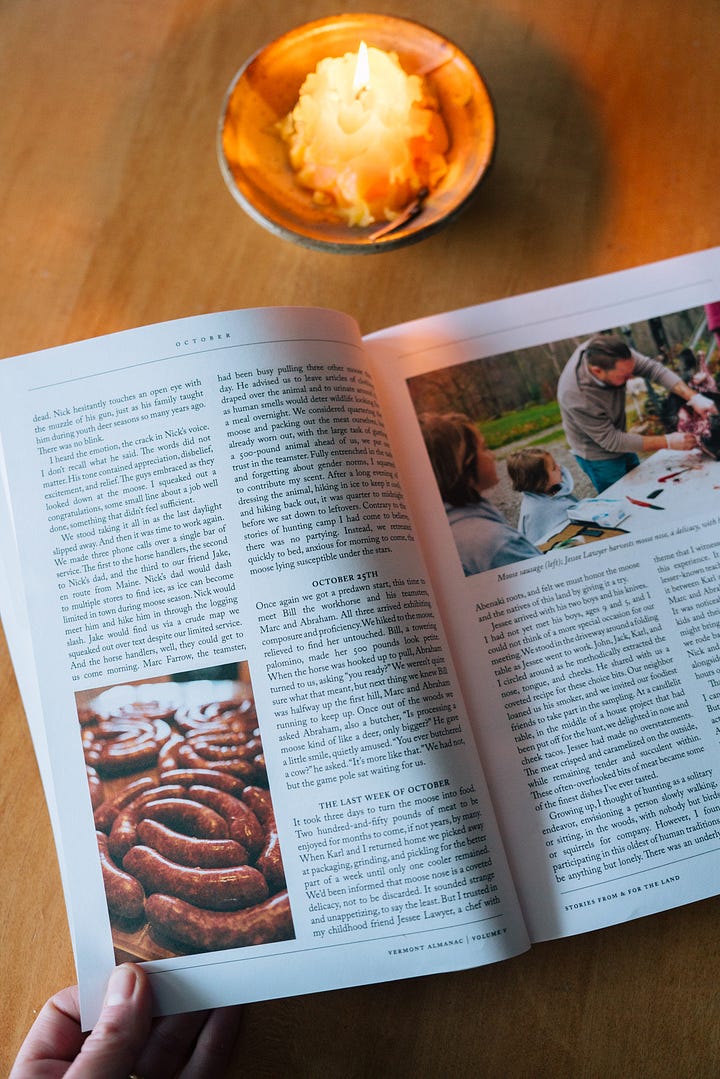

When my partner got his moose permit Jessee was clear that, should we have the opportunity, we would be remiss not to eat the nose. Skip mounting it he said - “what a waste.” As strange as eating nose might sound, I didn’t hesitate to take his word. First - he’s an executive chef. Second - I’m hunting on the stolen land of his ancestors. To be given the privilege of insight about this piece of meat calls for respect - for him, for the Abenaki, and for the moose. When we found success on our hunt Jessee made the trip to my rural home with his two boys, teaching us how to procure and prepare moose nose, tongue and cheeks. With Jessee’s guidance and some careful preparation we were gifted true delicacies, some of the finest meals of my life.

As Jessee and I rode to the book launch, he noted that it is time to tell the stories of our generation. He put this in perspective, explaining that we’ve heard the stories of our parents, and of our parents’ parents, but there is no denying we’ve reached the age of holding this responsibility too. He emphasized the importance of taking onus of this “…now, maybe more than ever.” I thought of what he taught me regarding the preparation of moose nose, aware that he was already doing the work of sharing, in both small and large circles.

We walked into the event and I recognized a characteristic I’ve noticed at many other gatherings in Vermont - an abundance of silver and white hair. We are in fact an aging state, one of the oldest in the nation. Still, I know there are younger folk here - at home tending to children, or perhaps merry making at a bustling bar, others winding down from the workday in front of a screen or with book in hand. Wherever they are, I noticed that they weren’t here, and I left the event wondering how to find their stories too.

Upon flipping through the Vermont Almanac, now sitting on my coffee table, I see the various faces and inscriptions of the many authors at the beginning of the book. Some have silver hair, yes, but younger folk are sharing too. To my delight I recognized the smiling face in a sunflower filled photo - my nurse colleague Suzanne. True salt of the earth, Suz is the type of person whose warm hugs and chocolate eyes invite you to share the honest parts of you, the ones you’ve buried deep down. In addition to being a nurse, she has worked hard to continue the traditions of her family’s farm, while adding her own twist to the offerings. Suz makes herbal elixirs as well as skincare products derived from tallow, which she sells from her apothecary: Loomis Hill Botanics.

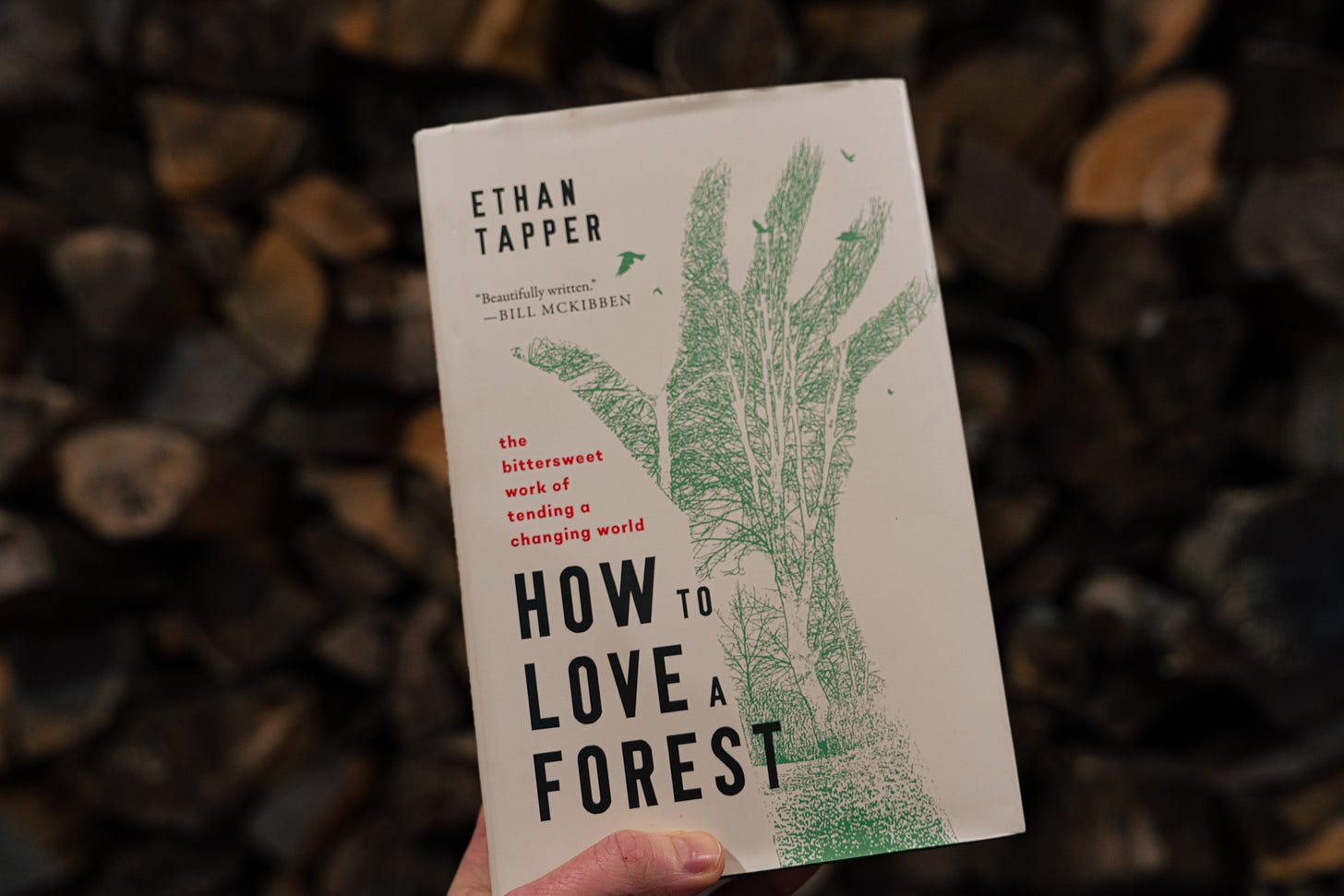

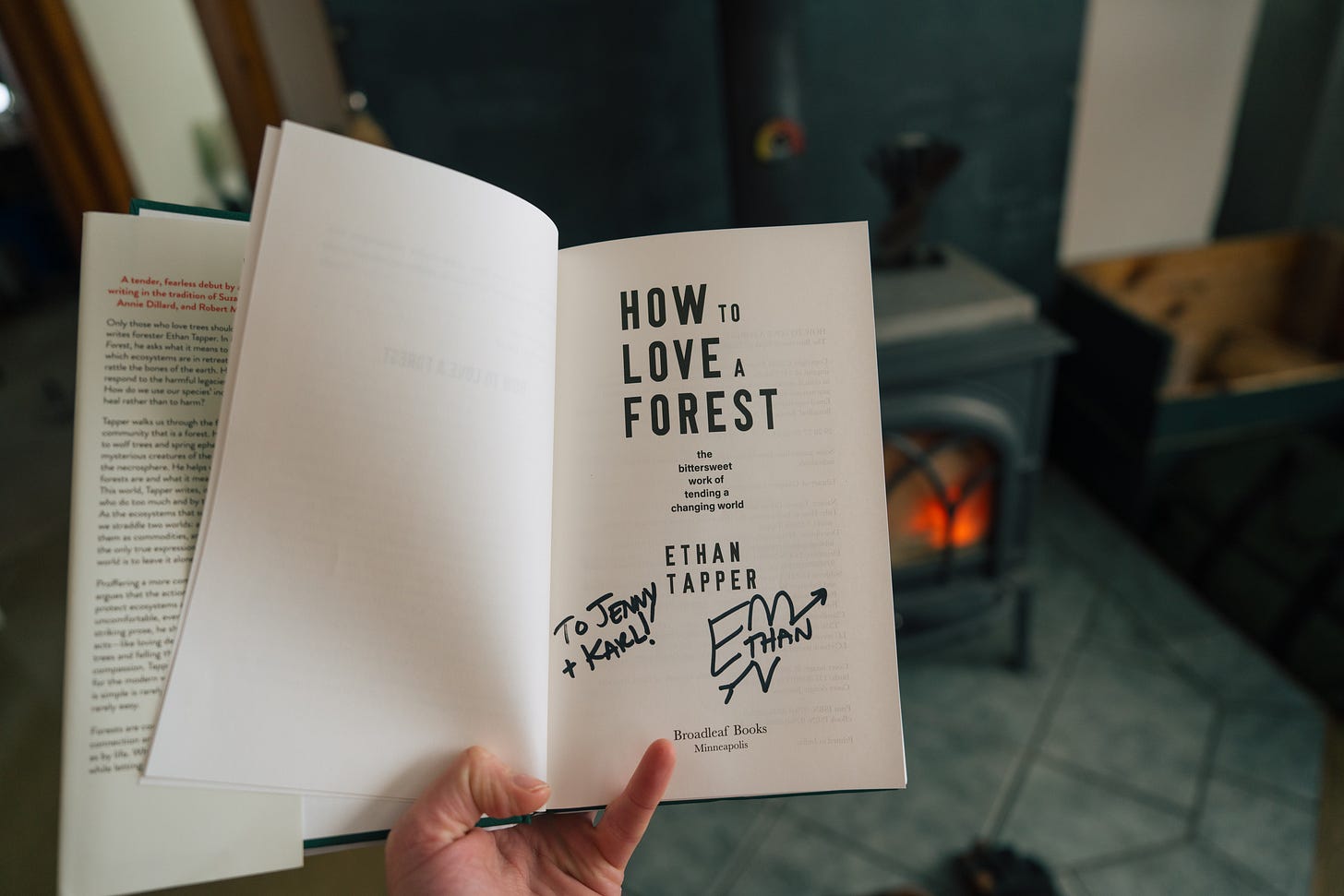

On another page I also recognized local forester Ethan Tapper, a fellow University of Vermont grad who recently published his first book “How to Love a Forest,” an excerpt of which is in the Almanac. I first met Ethan on an organized walk put on by my town’s conservation commission. We walked through a local public forest and Ethan shared the history of it by looking at the trees. He explained the clues as he saw them - the types of trees present, their prevalence, how they were growing. What was here? What was missing? His ability to read a place’s history by observing a wooded landscape was eye opening. I had always assumed the forests around me were pristine, just as they should be. I hadn’t realized the lasting effects from old human actions, such as clear cutting in the 1800s for sheep farming. It has taken me years to see that despite the woods’ beauty, the forest resembles nothing of what it did prior to colonization… that really, it needs present day humans to help it be healthy, to pick up the pieces from past human actions.

Ethan is a gifted communicator, taking complex ideas and sharing them in a way that is understandable, approachable, and just plain respectful. This lends itself well to having tough conversations about controversial topics such as cutting trees, managing invasive plants, using herbicide selectively, and the harvesting of doe to prevent over browse in our forest’s understory. These are not easy topics. It may seem counterintuitive to cut trees to promote the health of a forest, to use herbicide to protect our ecosystem, to kill deer to improve their own habitat. Humans can get emotionally charged when it comes to these matters. Instead of shying away, Ethan is holding space for these conversations, writing a book about the importance of action over apathy, explaining that in a world full of impossible decisions, the responsibility lies in making those hard choices.

On that first walk I attended with Ethan we attempted to smother a football field’s worth of invasive Japanese knotweed. I’ve heard the argument that this plant is now here for a purpose, for its medical benefits that can aid in the treatment of Lyme disease. I appreciate the tinctures, along with the antibiotics, that my partner took when he had his own most recent bull’s eye rash. I also can see that a whole field of native plants disappearing to one singular organism is something to pay attention to, as this is loss of habitat for hundreds of species, all of which play a role in the intricate web that we like to forget we rely upon.

Later that summer the conservation commission was considering the selective use of herbicide on invasive plants, by targeted application with a Bingo dauber to their cut stems, to promote the health of the forest. This is a technique selectively recommended by Ethan in situations where manual removal efforts are hopeless. The town lit up in controversy, our local online news bulletin on fire about this topic. How could applying herbicide to an ecosystem be a good idea? What was the local conservation commission thinking? Weren’t they supposed to be protecting the landscape, not applying poison? The oncology nurse in me cringed at the thought of herbicide, even in localized treatments. Conflicted, and with an aversion to controversy, I didn’t attend the public hearings in which our elected officials and Ethan held space for these charged conversations. I instead watched the debate from the comfort of my computer screen. I took the power I hold to affect this planet, and I chose to do nothing. Which we all know, is choosing something after all.

I recently finished Ethan’s book, and if I could recommend you read anything at all this year, I’d recommend chapter six of “How to Love a Forest.” In this day and age it is not easy to address healing our planet, our ecosystem, and to hold hope while doing so. There is so much at stake, so much that has already been damaged, and so many different viewpoints - some very righteous indeed. Ethan is showing up to make the tough decisions necessary to steward our forests, and he isn’t hiding his radical thoughts on it either. In a world of imperfect choices, he is sharing his story, realizing that if he moves just one person from apathy to action, he has found a win.

I wrote my own story in the Almanac in an effort to share a way of life I have come to appreciate, but feel is complex, often misunderstood. How could hunting be an action of caring and compassion, of sincere connection to other beings on this planet? Through my writing I aimed to convey the respect held for the animal, the raw humanity and relationships formed along the way, and the significance of the effort involved. As Ethan had, I hoped to reach even just one person… to illustrate the value of food from the field and sustainable sustenance as a respectable choice. In a world in which it is so easy to turn a blind eye to the implications of food and goods from far far away, I wanted to open the door for someone, anyone, to consider this option.

Of all the people I have to thank for getting the story onto paper, it may come as a surprise that it was my New York City born hair dresser that really got me there. A year ago I sat in Bonnie’s chair, acutely aware my audience may not hold a positive association with the concept of hunting. Something told me to take this opportunity to share, to tell her my moose hunt story, to explain what it had brought to our lives. Bonnie, to my surprise, wholeheartedly engaged as I explained the connections formed on the journey to obtain hundreds of pounds of meat that would fill our freezers. Through the sharing of this story our bond grew too. The next time I sat in Bonnie’s chair she told me of the conversations she’d had with others on this topic since our last meeting. Bonnie’s opinion on hunting had shifted. My story had stuck with her. When I told her about having a hard time writing it down, she encouraged me, told me to just write. And so I wrote the damn thing.

As I reflect, I think back to my teenage years, sitting outside our high school in Jessee’s red boxy ‘93 Dodge Shadow. I never would have thought I’d be calling him one day to ask how to cook a moose nose. I don’t think it’s something he even knew about back then. But somehow, along Jessee’s journey, someone shared the story of how to cook this with him, knowledge that surely originated in generations past, before cookbooks and websites, long before written language was prevalent in North America. It hits me that this expertise could have easily been lost, but someone shared it with someone else, who in turn shared it again, and eventually it was passed on to Jessee, who passed it on to me. It brings me to wonder where today’s stories could reach, now, and into the future, even if told just one-on-one. I hope you’ll take this as an invitation to consider your own stories, and the power they hold - if only you’d dare to share them.

Where to find the individuals, services, & goods mentioned above:

Jessee Lawyer: (cooking demonstrations and catering)

In person at Edelweiss in Stowe, & @thedawnlandkitchen (when he chooses to engage on Instagram, as he wisely takes breaks from social media)

Suzanne Woodard: (apothecary and farm store)

woodardsfarm.com & @woodard.suz

Ethan Tapper: (author, speaker, forestry & consulting, educational content)

ethantapper.com & @howtoloveaforest

Bonnie Ahl (for the best head massages & “hairapist” experience in the Burlington area, Vermont):

halo-vermont.square.site

Vermont Almanac: (which showcases stories of the land through the seasons, and is a wonderful coffee table book)

vermontalmanac.org

Please never stop writing, your appreciation for humans and the life experience we all have to share is deeply touching and very much needed. Thank you for the light you shine 🫶🏼